Reflections on the Society for the Study of Affect 2024 Conference from Greenleaf Scholar-In-Residence Irene Depetris Chauvin

I attended the Society for the Study of Affect (SSA) Conference in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, held from October 12 to 14, 2024. The SSA’s Conference is an academic event that, since 2015, brings together different scholars who work on affect theory.

The “affective turn” marks a shift in thought in critical theory by exploring the complex interrelations of discursive practices, the human body, social and cultural forces, and individually experienced but historically situated affects and emotions. Affect theory, or the critical study of feelings and emotions, enables the academic examination of emotional responses to real-world occurrences and structures that affect people. Personal — or felt — experience is foundational to understanding how people traverse the world as individuals and as groups. With a strong influence of feminist, queer, and gender studies, the study of affect has variously developed within and across a diverse range of academic disciplines, artistic practices, and research approaches.

In recent years, the world has witnessed a multitude of unsettling developments, including the ongoing reinforcement of settler colonialisms in multiple forms, the emergence of AI, the rise of fascist movements, increasing misogyny, transphobia, homophobia, racial and ethnic hatred, and unimpeded climate catastrophe, among other things. This present context serves as an urgent call and an opportunity to explore how affective configurations and their study can provide insights into power dynamics, ideology, information, and disinformation.

The four full days of the conference were structured around panel streams connected with the topics of PROMISES (Where might we find/create/conceptualize/enact the space-time of the "promise" in all that surrounds us?), IMPASSES (How might we direct seemingly inevitable dark futures into an impasse?), THREATS (How to engage with the tangle of affects in their midst of different threats?), and SETTLINGS (how affect sediments, how it sticks or clings to the contexts and histories of encounters and how can be also unsettled, detached from those situations?).

I participated in a two-day workshop entitled “IS THERE GEOPOLITICAL DIVERSITY IN AFFECT THEORY?” organized by Ana Pais. I chose this panel because, as a Latin Americanist, I am particularly aware that affect is always situated, and therefore, knowledge about affect is necessarily historical and culturally specific, even though “affect theory” was initially developed in the global north. One of the biggest challenges in affect research is developing adequate tools and methodologies to study specific objects, considering knowledge that is culturally shaped. In other words, embodied and affective knowledge can be crucial in advancing our understanding of affect, particularly diverse conceptual frameworks, but it demands cultural awareness and openness to affective nuances.

In this vein, I presented a paper entitled “Affective Materialities in Brazilian Film” to open a discussion about alternative genealogies of affect theory and cultural multiverses of affective experience. I aimed to contribute to a discussion about affect and the use of drawings made by Amazonian Indigenous people in documentary films. In Indigenous ontologies, there is a peculiar coexistence of beings that enables thinking about more-than-human entanglements and redefining the connections between materiality, perception and affect. I hypothesize that the experimental use of drawings in films activates the vibrant materialities of the indigenous world, exploring non-anthropocentric visual modes, and creates a tactile connection with a past that is ambiguously present through the affective cinematic aesthetics of individual frames. In other words, the “skin of the film” enables us to acknowledge affectively the multiple temporalities, scales, and processes of deep, stratified forms of violence, which operate through entangled forms of life-destruction –for humans and nonhumans alike.

I particularly enjoyed that in the workshop, we also considered different iterations of the far-right political affects, mobilization, and manipulation in Latin America. Situated affect theory requires us to attune our senses to the cultural and historical dimensions of affect. Some panelists acknowledged that we can learn to separate the visceral and historical aspects in expressions of the new right and consider ‘affective literacy’ as an ethical empowerment of our choices, thoughts, and actions. What was particularly moving was the discussion about how right-wing activists use the term ‘visceral’ to naturalize the violence and oppression of minorities, who are supposedly ‘protected by the artificial gender ideology.’ This discussion implies a reassessment of affect theory, as this academic field, heavily influenced by feminism and gender studies, has generally used affect studies to explain emancipatory instances. Now, ‘affective configurations’ are being used in the public realm to reinforce anti-egalitarian and post-fascist projects rather than to deploy or justify transformative ones.

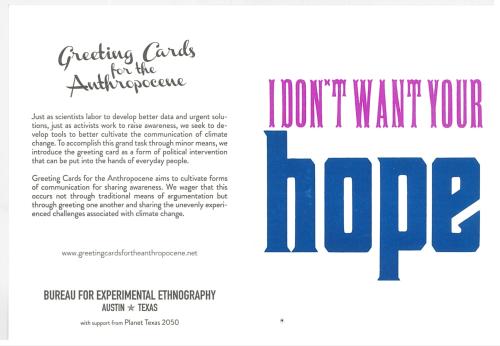

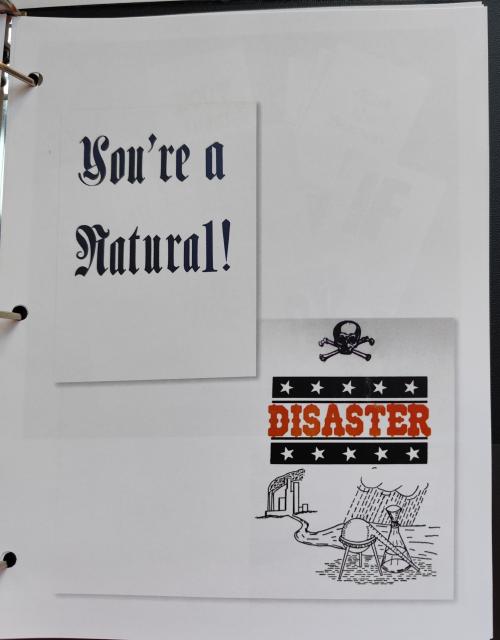

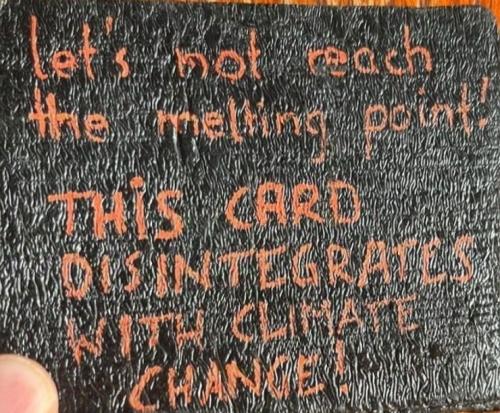

Finally, I also participated in various “Evocative activities” that included workshops, film screenings, collective crafting, and art and sound installations to engage in the topics discussed in the academic panels. For example, I was part of a group called “Greeting the Anthropocene” where we collectively experimented with language by adapting the conventions of greeting card exchange to explore our emotions about climate change, thereby helping us, through composition, to understand our feelings about the threats, culpabilities, hopes, incredulities, and paralysis of the Anthropocene catastrophic sublime. I also participated in “Smellworlds: Atmospheric Writing,” where we took a sample from a perfumery odor kit and submitted a short piece of writing provoked by the smells for an upcoming Smellworlds zine. We explore how olfactory knowing is both proximate and indeterminate, accommodating neurodiverse and more-than-human subjectivities, and discuss how scent textures theory can be used as a method for thinking broadly about affect, personal and collective histories, and memories.